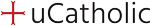

Throughout his life, Venerable Archbishop Fulton J. Sheen was renowned as a theologian and philosopher, but was most iconic for being a rarity in the realm of Catholic preaching. As a host on nighttime radio and later two television programs, “the golden-voiced Msgr. Fulton J. Sheen, U.S. Catholicism’s famed proselytizer,” had weekly audiences of up to 30 million.

Life Is Worth Living, his first television program, ran for 5 years starting in 1952 and featured Venerable Sheen speaking to the camera and discussing moral issues of the day.

One of his most celebrated sermons, “How to Have a Good Time,” was given on the show in 1957 and prophetically addresses the various maladies humanity faces in an increasingly secularized Western “ideal” that promotes worldly pleasures and eschews the spiritual.

In his sermon, he discusses the negative implications of our hectic society which incessantly concerns itself with the passage of time and the fear of being idle: a “restlessness of soul [that] translates itself into a restlessness of body.” This forms a root of unhappiness, as “the more conscious we are of the passing time, the less we enjoy ourselves.”

He talks of the constant need to “surround oneself with noise” to “drown out the consciousness of self and its passage through time.” Where silence would allow for self-reflection and a recognition of the consciousness, we seek out constant noise that keeps us “externalized,” to the end that we come to identify silence with emptiness.

Venerable Sheen also talks of the three keys to happiness in a world where seem to fight any real semblance of it: life, possession of Truth, and love.

You can read Venerable Archbishop Fulton J. Sheen’s full sermon on “How to Have a Good Time” where he elaborates more on the three keys to happiness below:

It is to be noted that almost everyone associates happiness or pleasure with time. Hence we speak of depressions, plagues, hot and cold wars as “bad times,” while pleasant companionship, good dinners and evenings out are identified with having a “good time.” Seneca has said “Time hath often cured the wound which reason failed to heal”; on the other hand, Doctor Johnson observes: “You cannot give an instance of any man who is permitted to lay out his own time, contriving not to have tedious hours.”

A “good” time is one of those catchwords which actually belies the true nature of happiness. The truth of the matter is that the greatest pleasures and joys come when we are unconscious of time.

The more conscious we are of the passing time, the less we enjoy ourselves. The clock watcher never enjoys his work. “Serving time,” a description of imprisonment, is synonymous with unhappiness and confinement. One prisoner who was sentenced to five years said to the judge: “I’ll not live that long.” The judge said: “At least, you can try.” Boredom is in part due to the inability to fill up time. People who overstay their time in visiting make one appreciate the reflection of Benjamin Franklin: “Fish and visitors smell after three days.” Once a visitor who had been standing on the doorstep for an hour, relating new items of gossip, finally said to her hostess: “I know there is something I forgot to say.” The hostess retoned: “Maybe it was ‘good-by?” The very phrase “killing time” signifies that existence in time can be depressing. A number of very obvious pleasures, and sometimes highly intellectual pursuits, are nothing else than “pass-times” by which man seeks to forget his temporality. The less conscious we are of the passing of time, the more we enjoy ourselves. In moments of sheer delight, we say: “The time simply flew”

Romantic love gets beyond time by eternalizing the present second; it makes time stand still, and tries to get beyond its succession by obliterating the past or future. The present moment of ecstasy, the dance, the music, the moonlight and a drive through the park, the joys surrounding graduation, all are rendered static; what is now will always be, without change or alteration. Movies, novels, short stories, and particularly narratives with passion as the theme, take a segment of life or time and, by an intense description of that moment, make it stand for life itself

A young woman once brought a young man to see her father. Her father objected, saying: “He earns only $25 a week.” “I know; Daddy,” she answered “but when you’re in love, time passes so quickly”

Another evidence of the connection between timelessness and happiness is found in the fact that the “old men dream dreams, the young men see visions.” Both old and young seek to escape the moment in which they live; the young look forward in hope to better days, the old look back in retrospect and memory to the “good old days.” The old man becomes, in the language of Horace, “laudator temporis acti.” Youth wishes to hurry time; old age tries to slow it down.

Time makes it impossible to combine our pleasures. It prevents us from making a dub sandwich out of the various enjoyments of life. The mere fact that I exist in time makes it impossible for me to march in the army of Alexander and in the army of Caesar at the same time; it forbids the simultaneous thrill of Alpine ascents and Riviera pastimes; I cannot sit down to tea with both Homer and Vergil, or enjoy simultaneously listening to Aquinas on philosophy and Da Vinci on painting. We often see signs by the roadway which say: “Dine and dance,” but no one can do both at the same time.

Temporal goods cannot be enjoyed all at once. The characteristic of the temporal enjoyment of various goods and objects is that they must be enjoyed in succession. Some begin where others leave off. When something new comes, something that we had before is taken away. We cannot have the ripe wisdom and the reflective serenity of maturity together with the impetuousness and the adventurousness of youth. All are good; yet none can be enjoyed except in the season of life appropriate to it. What is true individually is true socially. However much we may gain by what we call the advance in civilization, something has to be surrendered. For instance, our life is being made more secure, but with greater security there is a loss of adventure.

Real happiness brings together all the joys we have ever had, concentrating them in one focal point, bringing together the thrill of living at every second of existence from infancy to maturity; the joys of discovering truth, such as the scientist, the philosopher may have; the ecstasy of love, whether it be a patriot’s for his country, a priest’s for his Lord, a spouse’s for his spouse. To intensify all this happiness in one focal point we would have to be outside time.

Happiness then has something to do with escape from time. But there can be a true and a false escape from time. First, we shall concern ourselves with the false, or the neurotic, escape from time. Time necessarily implies consciousness, and consciousness implies responsibility. One of the joys of sleep is its delightful irresponsibility. False escapes from time have something to do with flight from the burden of self-existence and responsibility.

Doctor Adler, the psychiatrist, has said: “Time is the neurotic’s worst enemy and the degree of precision with which a man succeeds in solving the problem of time is one of the measures of his normality” A German philosopher, Franz von Baader, has written on The Sufferings of Temporized Man. Marcel Proust believes that time has a corrosive effect on us like “water of mineral springs on the objects immersed in it.” A Spanish philosopher, Diego Ruiz, says: Tempus est dolor. There are various neurotic ways of escaping time; one is by opiates, which here stand for all forms of inducing unconsciousness to the passing of time. The empty soul which feels its emptiness seeks to put itself in a state of irresponsibility. The futility, the sterility, the gnawing of conscience, all of which are incidental to existence in time, cannot be endured. The self can be forgotten only by getting outside of time or consciousness. The narcotic which dopes the hunger of the soul enables a man to escape both his own misery, which he knows, and his possible salvation, which he knows not. The overemphasis on the unconscious represents also a flight from self, not only because too much self-analysis tends to break up into tiny fragments the unity and autonomy of personality, but also because the unconscious is identified with that for which we are not responsible.

Another neurotic way of killing time is by surrounding oneself with noise. Noise drowns out the consciousness of self and its passage through time. Silence becomes unbearable, because it makes the self reflective; noise, however, keeps one externalized. The neurotic regards stillness as a privation of movement, and silence as a structural flaw in the everlasting flow of noise. Silence becomes identified with emptiness. The Greek word for school was schola, which means “leisure.” Education was inseparable from a certain amount of silence and freedom from pressure.

As Aldous Huxley wrote: “The twentieth century is among other things the age of noise. That most popular and influential of all recent inventions, the radio, is nothing but a conduit through which pre-fabricated din can flow into our homes. And this din goes far deeper of course than the eardrums, it penetrates the mind, filling it with a babel of distractions – news items, mutually irrelevant bits of information, blasts of corybantic or sentimental music, continually repeated doses of drama that bring no catharsis, but merely create a craving for daily or even hourly emotional enemas. Spoken or printed, broadcast over the ether or on wood pulp, all advertising copy has but one purpose – to prevent the will from ever achieving silence.”

Another neurotic escape from time is flight and speed.

The opposite of flight is leisure, which implies a quiet mind, in a comparatively stationary body. Almost all the producers of great art and thought have been stationary. Socrates never left Greece, and rarely Athens. Kant never left Koenigsberg. Leonardo da Vinci restricted himself to northern Italy, and Bach stayed permanently in Leipzig. Schubert spent most of his life around Vienna. Wordsworth, except for three years, remained in Westmoreland. Doctor Johnson staved in Lon don most of the time. Today, in contrast, many writers are expatriates: they have uprooted themselves from their countries as they have uprooted themselves from tradition. Their restlessness of soul translates itself into a restlessness of body. Incessant movement keeps them from making the greatest voyage of all – the discovery of self.

Max Picard says that our love of speed is a flight from God, a way of escaping the Great Pursuer, or what Francis Thompson has called “the Hound of Heaven.” The man of faith, when he takes to flight, enters into himself. Today, flight is purely external. Hence we try to speed through time in order to fly from our origins and to escape the dread of being driven back within ourselves and being confronted with the spirit. Thanks to speed, man has gained the illusion that all things are subject to him. Like a mighty conqueror, lie mounts his chariot, and all things pass by. In a world of faith man knows that God is everywhere. As the Psalmist put it: “If I go to hell, even there His power is present, if I go to Heaven, there He reigns.” In darkness, in flight, and in repose, God sees and knows me. By flight and speed, man hopes to escape this ubiquity of God. God is permanence amid man tries to escape Him by constant change and movement. Speed, for the neurotic, is not something physical, it is some thing mental. This is not just a love of objective speed, but of subjective speed. It is a way of affirming his egotism through an identification of the ego with the power of the machine. It seems to annihilate time, but wholly in a neurotic way.

If time is an obstacle to true happiness, because it makes it impossible for us to combine our pleasures, it follows that the only way we can be really happy is by completely getting out¬side time, so that there is no “before” or “after,” but, in the descriptive Latin words, tota simul. Tota: all enjoyments of which our personality is capable. Simul: simultaneously, that is, without any succession.

If happiness consists in transcending time, it follows that no complete happiness can be found until eternity, when there will be a total fulfillment of the deepest aspirations of the soul. But what are these? Suppose each of us could take out his heart amid put it into his hand as a kind of crucible, to distill out of it its inmost yearnings and aspirations; what would he find them to be?

The first condition of happiness is life, for what good would riches and power be without the life to enjoy them? And the life we want is not for five more minutes or five more years, but always – an endless, ageless, timeless life.

The second requisite for happiness is the possession of truth. We were made to know. But it is not so much truths we want to know, not isolated bits of information, but all truth – not, for instance, the truths of science alone, to the exclusion of the truths of theology, or literature, or music, but total truth. To be happy, our mind must be bathed in light and knowledge and for this we must perceive truth, not in fragments, but altogether in some complete and timeless perception.

The third requisite for happiness is love. It is not good for man to be alone. But this love must be timeless; therefore it must not age, or decay, or lose its ecstasy.

Though these are the conditions of happiness, we find that all of them are made impossible by the mere fact that we are in time. Life in its fullness is not to be found here, because here in time life is mingled with death. Neither is truth found here. Consider how often the prejudices of youth are corrected by study; how often those who come to mock remain to pray; how often, too, the more we study the less we feel we know, because we see the new avenues of knowledge down which we might travel for a lifetime. Neither is love in its fullness here, for while we are in time, love has its moments of satiety; even when love does remain fine and noble, a day must come when the laborer’s shoulders are unburdened, the last embrace is passed from friend to friend. Nothing that ends can be perfect.

None of these conditions of happiness is to be found totally and completely here. But we are not to be cynics and say that happiness does not exist at all, for if there is a part there must be a whole, if we have a shadow there must be a light. It is like looking for the source of light in a television studio. It is not to be found under the cameras or the desk, for in those places, light is mingled with shadow. So, too, our reason tells us that we, if we are to find Life amid Truth and Love, must go to a Life that is not mingled with its shadow, death; to a Truth that is not mingled with its shadow, error; and to a Love that is not mingled with its shadow, hate. We must go out to something that is Pure Life, Pure Truth, and Pure Love; that is the definition of God, and the possession of God is happiness.

Photo credit: Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons